In Defense of Asteroid City

The desire for praise and achievement can hinder our creative expression. Asteroid City’s criticism should remind us that art will always be subjective, and sometimes doing “too much” isn't always a bad thing.

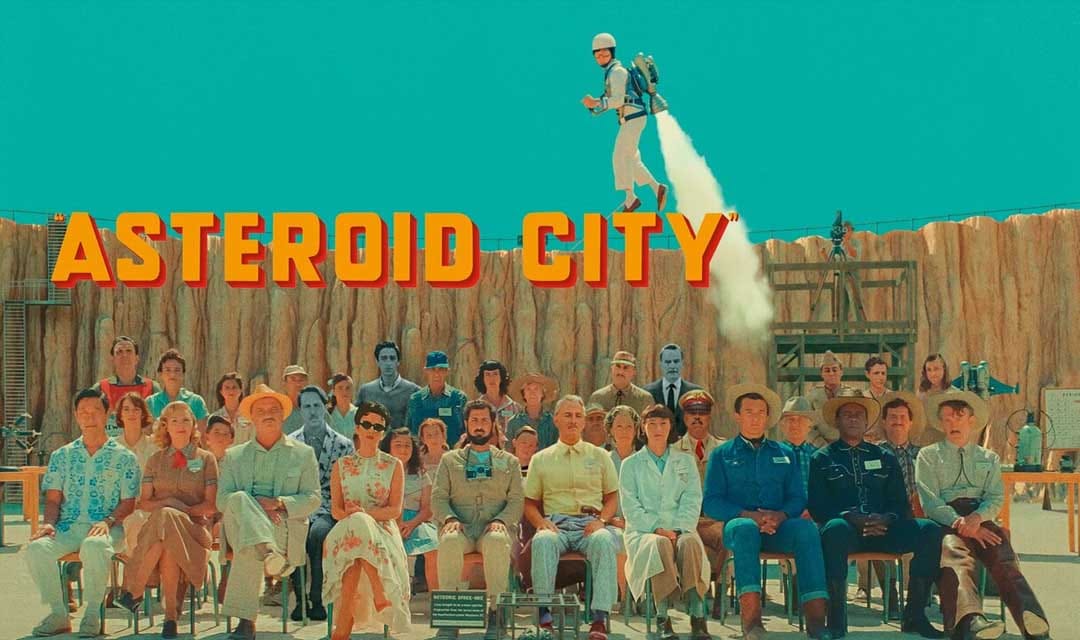

It's easy to be swayed by the majority. External sources tell us something is bad, and sometimes, these sources are loud enough that we start to believe them, even if we don't feel the same deep down. This instance is common in the film community, but sometimes, you can be touched by something so deeply that you just have to defend your opinion, even when you think it might be better to just shut up and move on. I loved Asteroid City (2023), and I'm not afraid to say it. I refuse to be passive any further, acting like my fondness is some dark secret, even though my taste in film is questioned the second I reveal it. I'm no Anderson aficionado, and I think this is exactly why I find myself drawn to the film. I turned it on with no expectations, my bar not set implausibly high, and I found myself charmed by every aspect of Asteroid City’s desert settlement and its strange, fleeting inhabitants.

The film begins by displaying what is, in short, a play within a play within a play. The dramatic camera pans and vintage coloring within Asteroid City, a glorified rest stop just off the site of a meteor crater, is the deepest level of the film's meta. Beyond this production are the outer layers of the film, which is the reality outside of the play, following the directors, actors, etc, and the reality even further outside that. These layers don't just serve as a quirky plot formation, one that's meant to amplify confusion just for the sake of it. Each individual tier of reality helps flesh out and build the deeply philosophical themes embedded into the film, creating a beautiful display of the human condition and how grief and desire bleed into every aspect of our lives. Asteroid City is heavily interpretable, and part of what I think the film does well is that it doesn't waste time explaining what we're watching or what exactly they want the audience to take from the film. It gets straight to the point and trusts the audience to follow along. While some people dislike this, unable to resonate with the film because they couldn't make sense of the layers within it, I enjoyed how the film worked a bit like a puzzle. You have to do some work to sort it out, but once you do, it's all the more satisfying to steep yourself within.

The off-kilter dialogue asserts the film's inherent absurdity, cementing its existentialist themes, and while some found the cold, unvarnished tone to be undermining and overkill, I found that, alongside the humor and lightness it granted the film, the dialogue created the perfect vessel for their thematic subtext to thrive within. Characters within the film’s central meta will say lines and then literally express the emotional motivation of their characters, to the point where the entire fictitious production feels refreshingly smug and self-aware. Even though personas do not attempt to convince you of their existence, which I think is the usual goal of any film, they still won me over, and I was invested in every version of a character displayed throughout the meta.

What I find so interesting about the reception of Asteroid City is that, ratings-wise, it didn't do badly. With a current Rotten Tomatoes score of 76% and a letterboxed rating of 3.5/5, perhaps it wasn't particularly loved, but people seemed to enjoy it. However, every time I bring it up, all I get is a relentless stream of judgments. While Wes Anderson is known for constructing these strange, idyllic worlds, where plot is nothing more than a humorous suggestion, it seems that the extremes Asteroid City takes this to were unappreciated. Accompanied by the exceptionally monotonous dialogue, fans found that, unlike his other films, they weren't left with anything and felt that aesthetics took precedence over plot, substance, and basic clarity. People just didn't seem to get it, and it can be hard to enjoy a film that doesn't make sense. I'll admit that this take is hard to argue against, but at the same time, I don't think we always have to understand things, especially not art. When this exact message seems to be relayed in the film, understood when Augie (Jason Schwartzman) says, “I still don't understand the play,” and is told, “You don't have to. Just keep telling the story,” it becomes clear that clarity is not the films priority, and that perhaps they are purposefully making a commentary about our dependency on it.

Ultimately, the complaint that takes precedence is that Asteroid City is just too “Wes Anderson.” Critics have called it a parody of his own directorial style, its narrative too overloaded with diversions, its cinematography austere in its exaggeration. What I find unappealing about this argument is that Asteriod City seems to be regarded solely by what comes before it. It's hard to separate a director from his past works, especially when Wes Anderson’s films often display themselves as a collective body. When a director you enjoy releases something, naturally, you wish for it to exceed whatever you last watched that set the standard. A piece of art shouldn't be defined by its creator or what comes before it, and I fear we are so deeply attached to pre-disposed ideas of directors that we let this consume our impressions. I find this notion to be repetitive within the film community, and I hope that we can adopt a more objective perspective, one that lets us watch a film without bias.

I think the deeper issue that's brought up by Asteriod City being too “Anderson” is that we've become acclimated to a culture where something's worth is measured by its ability to be universally appealing. We dislike something when it pushes the limit, even if that extreme is an embodiment of a person's creative ingenuity. I certainly enjoy the privileges of free speech, and this isn't to say that criticism or opinion isn't beneficial, but that it's important we pay attention to what we are actually saying about film when we do critique it.

Due to the increasingly commercialized environment of the film industry, I think we often forget that film, at its core, is not an enterprise but an art form. It is a medium of imaginative expression, and more often than not, it feels like films aren't being made for this reason anymore. Our urge to create has become somewhat perverted, no longer driven by passion or purpose, because we are possessed by the need to succeed, to be praised for our work, rather than fulfilled by its creation.

When we criticize Asteroid City for being too “Wes-Anderson,” we encourage the notion that creativity and peculiarity have their limits. By bringing his artistic distinctiveness to the next level with the film, Wes Anderson was taking a risk, creating an embodiment of his recent filmography and taking it to the extreme. Art is always going to be subjective. Even if you set out to make a film that you think would be universally adored, it can't be, and while there may be times to appeal to an audience, that should never be the main goal. In a creative industry, one must create what they want to, following their own passions and interests, because no matter what you do, people will always have their own opinions and objections, especially when presented with something different and unconventional. Wes Anderson is known for his distinct style, and even though some may see it as too much, it's important that we recognize the irony of that statement, understanding that this criticism shouldn't be the reason not to push your creative limits.

When risks are taken, they always pay off, even if it doesn't seem like it. By taking that risk, even when the majority of voices are negative, you create the ability to truly touch and affect people, even if they are the smaller margin. Asteroid City changed the way I think about grief and how it presents itself, and this positive impact happened through the exaggerated medium he created, in the extremes and peculiarities that took over the narrative. The film's influence on me was only possible because of the film’s most contentious aspects, and this emphasizes how one must sometimes forego mainstream appeal to create the art you want, even if it isn't always understood at first.